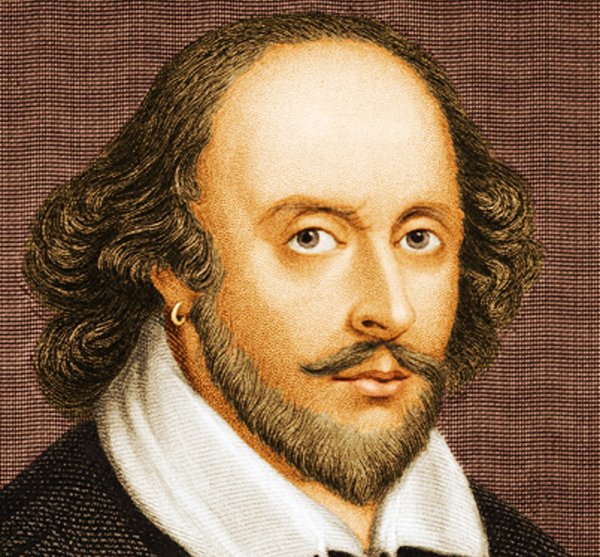

William Shakespeare 26 April 1564 (baptised) – 23 April 1616)

LISTEN

After listening to this piece by Handl I feel as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own.

The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1610–11, and thought by many critics to be the last play that Shakespeare wrote alone. It is set on a remote island, where the sorcerer Prospero, rightful Duke of Milan, plots to restore his daughter Miranda to her rightful place using illusion and skilful manipulation. He conjures up a storm, the eponymous tempest, to lure his usurping brother Antonio and the complicit King Alonso of Naples to the island. There, his machinations bring about the revelation of Antonio's lowly nature, the redemption of the King, and the marriage of Miranda to Alonso's son, Ferdinand.

Think of a being who has never seen

a man or woman, never looked in wonder at the

the elfishness of a child, never stood in awe at the beauty of girlhood, and never witnessed benign philosophy of old

age. That might be Caliban in The Tempest

In the Tempest we witness Sahakepsere's catholicity of taste in a quest for fact.

and Shakspearian alchemy ballasted with fact.

When Hamlet reflects on the absurdity of life, when the Duke counsels Claudio that death is to be welcomed, when Lear sees in Poor Tom a general truth about 'unaccommodated man', it is very possible to find parallels - sometimes slight, sometimes striking - in Montaigne.

To demonstrate influence in such a tricky case, one would need to emphasise the element of similarity. The real interest of the comparison lies, however, in the divergence it reveals, for the Montaignean vision of radical naturalness, of unaccommodated man, both fascinates certain of Shakespeare's characters, and generates a kind of recoil. Thoughts which Montaigne embraces as salutary and humane, as fostering a profound toleration of the nature of human life, become in their Shakespearean context radically destabilising, markers of an intolerable distress, often associated with cynicism or disgust

Both the engagement and the recoil can be felt in The Tempest, and may be summed up in the statement that Montaigne's splendid cannibals become Caliban - although we must remember that we never meet Caliban in his original, natural state, but only as Prospero's expelled pupil and rebellious slave. There are two accounts of how he came to be what now he is, and Shakespeare gives us no way back to adjudicate between Caliban's own, sufficiently Montaignean, claim that he has been corrupted by his education, and Prospero's insistence that he was, from the beginning, 'a born devil'; neither witness speaks disinterestedly

In 'Of Cannibals' Montaigne knew well enough that the New World could hardly be a role-model for the Old. But the vitality in the essay expresses the sense that what has been discovered in America uncovers a real potentiality, of which the bare idea is enough to alter the Old World's sense of itself forever. Gonzalo's idea, however, is Utopian in a way which cannot act upon experience, for it omits too much - it is too 'innocent' - for its rehearsal to touch any reality:

Gonzalo. And, - do you mark me, sir? Alonso. Prithee, no more; thou dost talk nothing to me.

Montaigne's affirmation of a radical naturalness, of the sovereignty of our 'puissant mother Nature', cannot be so vigorously affirmed in Shakespeare;

No comments:

Post a Comment