As Heidegger frequently points out, in the modern, post-Cartesian world, an “object,” Gegenstand, is something that “stands opposite” a human subject, something external to subjectivity.

In order to experience an object, the modern subject supposedly must first get outside the immanent sphere of its own subjectivity so as to encounter this “external” object, and then return back to its subjective sphere bearing the fruits of this encounter.

Given the modern subject/object dichotomy, such an adventure beyond subjectivity and back again is required for the experience of any object. But in the case of the art object, Heidegger is pointing out, the adventure beyond subjectivity and back again is a particularly intense, meaningful, or enlivening one: A “lived experience” is an experience that makes us feel “more alive,” as Heidegger suggests by emphasizing the etymological connection between Erleben and Lebens, “lived experience” and “life.

seems to be that once aesthetics understands artworks as objects of which we can have meaningful experiences, it is only logical to conceive of these art objects themselves in an isomorphic (similar in form and relations) way, as meaningful expressions of the lives of the artists who created them.

After World War I started

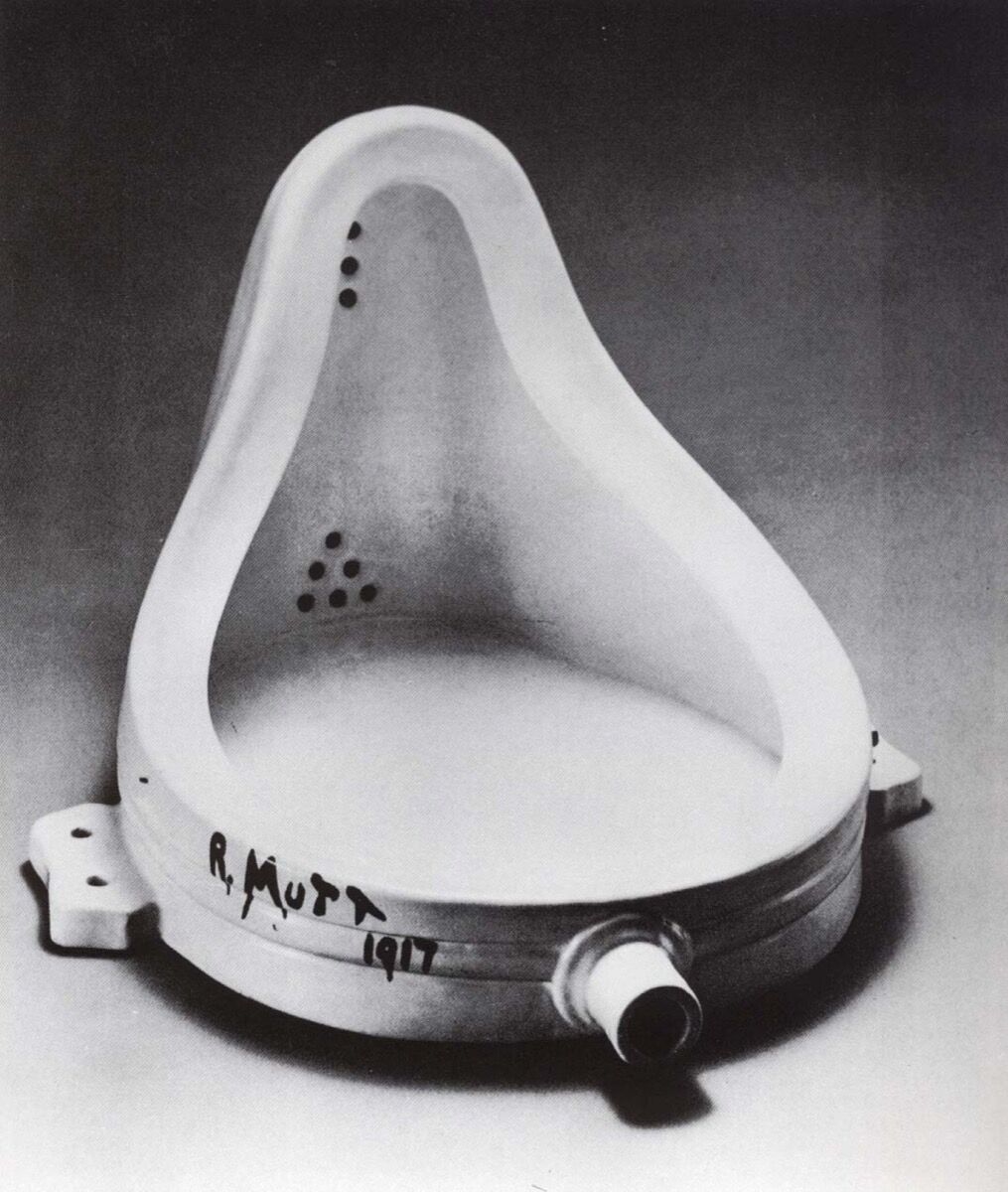

Still, this alleged isomorphism of aesthetic “expression and impression” is not immediately obvious.[Think, for example, about the seriously playful “found art” tradition in Surrealism, dada, Fluxus, and their heirs, a tradition in which ordinary objects get seditiously appropriated as “art.” (The continuing influence of Marcel Duchamp’s “readymade” remains visible in everything from Andy Warhol’s meticulously reconstructed “Brillo Boxes” (1964) to Ruben Ochoa’s large-scale installations of industrial detritus such as broken concrete, rebar, and chain-link fencing, such as “Ideal Disjuncture” (2008). Vattimo thus suggests that Duchamp’s “Fountain” illustrates the way an artwork can disclose a new world, a world in which high art comes to celebrate not only the trivial and ordinary but also the vulgar and even the obscene.) This tradition initially seems like a series of deliberate counter-examples to the aesthetic assumption that artworks are meaningful expressions of an artist’s own subjectivity.

How Duchamp’s Urinal Changed Art Forever

Image of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, 1917, via Wikimedia Commons.

No comments:

Post a Comment