A nice weekend in Sussex with friends in which their dog played a large part. Got me thinking of....

The Language of Animals

"An Apology of Raymond Sebond", in The Works of Michel de Montaigne, 1865

translated by William Hazlitt

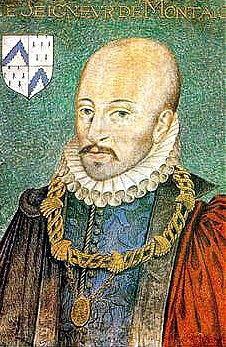

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (French pronunciation: [miʃɛl ekɛm də mɔ̃tɛɲ]) (February 28, 1533 – September 13, 1592) is one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance, known for popularising the essay as a literary genre and is popularly thought of as the father of Modern Skepticism. He became famous for his effortless ability to merge serious intellectual speculation with casual anecdotes[1] and autobiography—and his massive volume Essais (translated literally as "Attempts") contains, to this day, some of the most widely influential essays ever written. Montaigne had a direct influence on writers the world over, including René Descartes[2], Blaise Pascal, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Friedrich Nietzsche, Stefan Zweig, Eric Hoffer[3], Isaac Asimov, and perhaps William Shakespeare (see section "Related Writers and Influence" below).

In his own time, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. The tendency in his essays to digress into anecdotes and personal ruminations was seen as detrimental to proper style rather than as an innovation, and his declaration that, 'I am myself the matter of my book', was viewed by his contemporaries as self-indulgent. In time, however, Montaigne would be recognized as embodying, perhaps better than any other author of his time, the spirit of freely entertaining doubt which began to emerge at that time. He is most famously known for his skeptical remark, 'Que sais-je?' ('What do I know?'). Remarkably modern even to readers today, Montaigne's attempt to examine the world through the lens of the only thing he can depend on implicitly—his own judgment—makes him more accessible to modern readers than any other author of the Renaissance. Much of modern literary non-fiction has found inspiration in Montaigne and writers of all kinds continue to read him for his masterful balance of intellectual knowledge and personal story-telling

No comments:

Post a Comment